Dear Readers,

You might wonder if I regret spending the last decade training to become a lawyer instead of a creative writer. I don’t.

Who knows what career decisions I would have made ten years ago if I knew myself better? If I had more courage? If I wasn’t chasing prestige? If I didn’t prioritize financial security over joy?

It doesn’t matter, because the truth is, I have no regrets.

Becoming a lawyer came at a high cost.

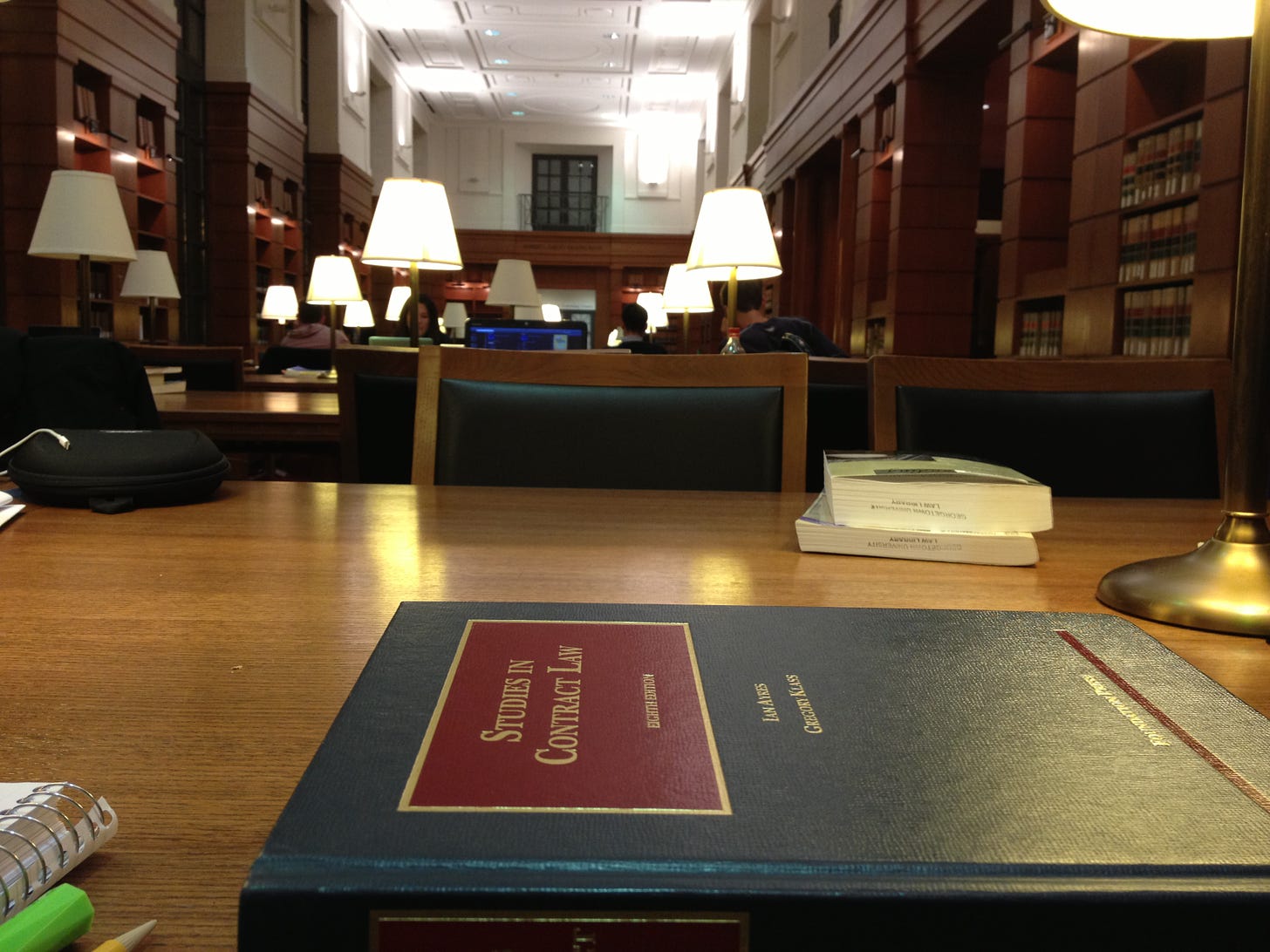

I graduated with six figures of law school debt. The full impact of that albatross didn’t really hit me until my first semester. That’s when I first overheard my peers anxiously speaking in hushed whispers at the law library about needing to beat the grade curve. Students in the top 10% of the class got the cushy BigLaw salaries that could justify the high cost of tuition.

Law school also took a heavy emotional toll. At one point in my second year, I found myself mildly depressed. I felt like I was moving underwater, and it look a lot of effort just to show up for lectures. With the help of a therapist, I eventually found my way out. I think some part of me knew that being a lawyer wasn’t really the right career path for me. But I had already made a big bet with the law school loans—I was in too deep to fold.

I’m glad I didn’t quit.

After law school I spent seven years trying to make a legal career work for my brain and my body. It wasn’t a great fit. But I gave it the good ol’ college try. And my reward is: I know I gave it everything I could. I also learned some skills that are helping me now an aspiring novelist.

Law school taught me how to tame the wild horse that is my mind.

I am not a linear thinker. My head is a walking brainstorm. Writing exactly the way my mind moves would be like writing in several different languages with 18 timelines and 12 points of view. Does that sound insane? (If so, examine your own mind and then come talk to me.)

Law school made me deconstruct my brain and build it back up again in a way that could be used to form cogent arguments. I now have a mind that can ace LSAT logic games.

Logic games for the Law School Admission Test (LSAT) generally involve an overarching scenario and a series of rules. You have to deduce what must be true based on the rules. It’s sort of like a puzzle or a riddle and requires very organized thinking. Several logic games have to be completed quickly to earn a high score on the LSAT.

A typical game is like the below. (Don’t read it word for word, just skim it to get a flavor of what kind of thinking is required.)

(Adapted from a June ‘07 LSAT question)

Three films called Glory, Hedonism, and Lyrical are shown during a film festival held on Thursday, Friday, and Saturday. Each film is shown at least once during the festival but never more than once on a given day. On each day at least one film is shown. Films are shown one at a time. The following conditions apply: - On Thursday H is shown, and no film is shown after it on that day. - On Friday either G or L, but not both, is shown, and no film is shown after it on that day. - On Saturday either G or H, but not both, is shown, and no film is shown after it on that day. Which one of the following could be a complete and accurate description of the order in which the films are shown at the festival? (A) Thursday: L, then H; Friday: L; Saturday: H (B) Thursday: H; Friday: G, then L; Saturday: L, then G (C) Thursday: H; Friday: L; Saturday: L, then G (D) Thursday: G, then H, then L; Friday: L; Saturday: G (E) Thursday: G, then H; Friday: L, then H; Saturday: H (If you’re curious, the answer is C).

The LSAT logic game section was the hardest nut to crack for me. I’d get angry because I thought these games had nothing to do with being a lawyer. But I now know that the games accurately capture the type of thinking required for law practice.

In law school and in law practice, I learned to think and analyze systematically, rather than in the free-flowing, idea-blooming, connection-making manner my brain tends to operate.

Why is this good for creative writing? A novelist’s world needs internal logic. If Harry Potter knew how to use his wand right out of the box, going to a magical school wouldn’t make sense. Any fantasy author will tell you that a magic system’s rules must be internally consistent, otherwise the reader gets thrown out of the book-world. Readers can only suspend disbelief so much.

Law school and law practice grew my brain’s capacity to spot inconsistencies in how rules are applied, i.e. how the world works. That’s a helpful skill for fictional world-building. The rules and consequences in my novel’s made-up world are coherent and logical, which allows a reader’s imagination to dive deeply into the story and stay there.

Lawyering helped me become a better overall writer.

Surprised? I am too. Legal writing has the reputation of being mind-numbingly erudite.

Lawyers do not actually want to sound like they’re writing jargon and gobbledygook. Legal writing is so difficult to read because the law is complicated. We try to make it as clear as possible, but the effort to be precise (necessary for law) sometimes means describing minutiae you could typically leave out in internet essays.

Consider this paragraph from Brown v. Board of Education:

We conclude that, in the field of public education, the doctrine of “separate but equal” has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal. Therefore, we hold that the plaintiffs and others similarly situated for whom the actions have been brought are, by reason of the segregation complained of, deprived of the equal protection of the laws guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment.

Here’s one way to make this paragraph more concise:

Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal. We hold that the plaintiff class complaining of segregation has been deprived of equal protection of the laws.

It works, but do you like it as much? Is some meaning lost?

In law school and in practice I learned to write as simply as possible without robbing my words of meaning. My writing is trenchant (I hope). It can be convincing while engaging, it can be pointed while flowery, it can be direct while dabbling in metaphor.

Law school taught me my absolute limits.

Being in debt made me empathize with Sisyphus pushing a boulder up a mountain only to have it roll down again. I mentioned above that law school deconstructed my brain. That process was painful.

I woke up every morning battling my will. I’d have to spend the day reading dense texts and sit in class pretending to understand what was going on. I’d pray that I didn’t sound like an idiot when cold-called.

Every evening I’d push myself to read more cases but many times my willpower broke, and I’d watch episodes of Parks & Rec instead. On Saturdays and Sundays, I’d debate with myself about how much more Constitutional law or Property law or Contract law my brain could absorb while sitting for hours in the law library.

It was hard. Some people enjoy law school. I did not. There were several occasions where I turned down or cancelled plans to be out and about in DC with my friends because I was still at the library studying, or still at the library trying to study but instead reading articles about productivity on the internet.

I also have ADHD and was undiagnosed at the time. (A little-known fact about myself that probably deserves several of its own posts). Extended bouts of concentration on a subject that has little inherent interest to me is like forcing myself to hold my breath under water over and over and over again. I can go longer with practice, but there’s only so much air my lungs can hold at a time.

Despite all my efforts, I still had middling grades in my first year of law school. In my third year I finally started getting top marks, but grades didn’t really matter by then. It took me three years to figure out what the hell “thinking like a lawyer” meant and how to do it.

But all the fighting with myself to apply my brain and body to a task that I was just not well-equipped to do taught me just how far I could go. I learned there really is no end to how much you can study and work. The only cost is depression.

I figured out my edges. How far could I go without my mental health falling off a cliff? Only way to find out was to fall off that cliff. And I did.

So now I have perspective. When I’m up against seemingly impossible tasks. I know what I can do and what I can’t. I don’t beat myself up for not being as good at something as I wish I was. For not spending as much time as I wish I could. For not making the effort some are capable of.

I know when I did my best. Like truly, truly, my best. My best is however much I can give until I get to the point where I’m disastrously unhappy. I walk right up to that line and then I stop.

There are several other gifts that practicing law gave me. But I’ve been going on for a while here.

What are you edges? Do you know when to stop working? When you’ve done your best? Let me know in the comments.

See y’all next Tuesday.

Noor

I really enjoyed reading this. When I was studying for the LSAT, the logic games were the hardest, but I did enjoy the challenge.

I also love the connections you made between thinking as a lawyer and a fiction writer.

I burned out pretty badly after two years of graduate school. I pushed myself so hard that I was successful, graduating with a 3.8, but I learned my limit and vowed never to push myself that hard again.

Knowing your limit is so important, and it's something I don't think we talk about enough.